How far do you plan ahead?

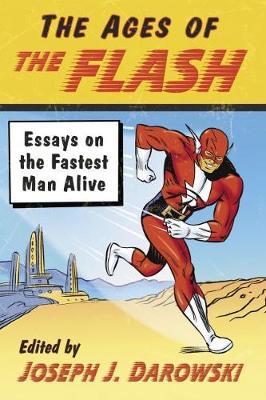

Later this month – February 28, 2109, to be exact – a book is coming out that includes a chapter by Yours Truly. (Shameless plug alert!)

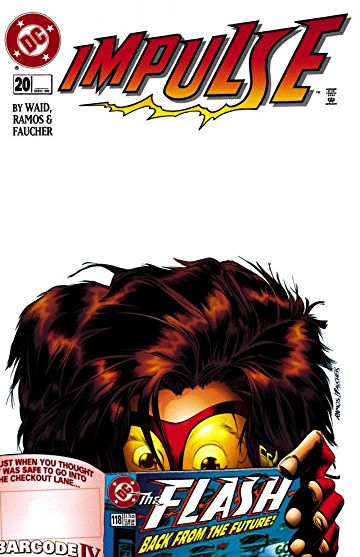

In the previous post, I shared an overview of this book chapter featuring teaching approaches of the Flash (Wally West) and Max Mercury, and the impact on their student Impulse. For now, though, let’s turn out attention to time travel.

Bart Allen (Impulse) is a 30th century teen transported to late 20th century America. The featured Flash and Impulse comic book stories in my book chapter were published in the mid 1990s. But this isn’t the kind of time travel I want to discuss.

Let’s look at the timeline of academic publication, using my Flash book chapter:

- April 2017 – I submitted proposal for book chapter.

- July 2017 – Proposal accepted.

- November 2017 – Chapter manuscript submitted.

- February 2019 – Book published.

Altogether, the process from proposal to publication is nearly TWO YEARS. And this isn’t even counting the original call for submissions, formulating my idea, doing the research (reading, looking up, reading, collecting data, reading, analyzing data, etc.), as well as the actual WRITING of the 25+ page first draft.

Two years from proposal to publication is actually about typical for most printed books. (That’s why it’s tricky for a writer to chase trends; by the time anything gets published there’s a new fad taking the world by storm.)

But to be honest, I had to stop and look up some of the above dates in my records. If you had asked me before, I probably would’ve thought the time period was much quicker. Time flies when you’re having fun (i.e. doing scholarly research with comic books).

Teachers also experience interesting time travel in their classroom work. And like publishing, the educational process can stretch along with many delays. A recent article on Edutopia talks about the long-term impact of teaching. Here is how it summarizes the featured research:

Teachers who help students improve noncognitive skills such as self-regulation raise their grades and likelihood of graduating from high school more than teachers who help them improve their standardized test scores do.

Later, the article addresses the predicament: Standardized tests don’t typically measure long-term teacher impact on things like self-regulation and other “noncognitive skills.”

Countless times, teachers reiterate that if something is important, you have to test it. Using reverse logic, we often assume that only the important things are on tests.

We can’t overlook those things that may be more difficult to assess or standardize. In the face of regular evaluation reports, teachers must keep the far future in view.

I would argue that these two outcomes – short-term test scores, long-term impact – are not mutually exclusive. Teachers can promote both at the same time, intertwined together.

Take publishing, for our ongoing analogy.

While this Flash book chapter has been moving toward publication, I’ve been busy working on other projects. Journal articles and conference presentations have faster turnaround times, and I’ve done both in the past few years.

Likewise, I have a new chapter in progress for the next “Ages of . . .” book. This one is about Marvel’s Black Panther.

My chapter deals with T’Challa’s demonstration of 21st Century Skills in defending Wakanda from the alien Skrulls’ Secret Invasion. If that sentence doesn’t excite you, maybe these comic book panels will . . .

So far, here is the timeline of my chapter:

- May 2018 – Submitted chapter proposal.

- August 2018 – Proposal accepted.

- January 2019 – Submitted chapter manuscript.

- ??? – Publication???

Right now, I’m awaiting feedback and requests for revisions from the editor. After that should be official news of acceptance and publication. But I’m not holding my breath. It’ll happen eventually.

In the meantime, there are always more opportunities to learn, write, research, and share. And enjoy the future possibilities!